Jonathan Harries’ THE TAILOR OF RIGA starts out innocuously enough: in researching his family history, the narrator, who has the same name as the author, finds out about his connections to Plungė, Lithuania, via forbears on his mother’s side, and also to Riga, Latvia, via his paternal ancestors. But things get weird fast, with this innocent-enough genealogical inquiry giving rise to a spate of unsettling family mysteries. Why is it that the narrator’s paternal great-grandfather, Abram Isakowitsch, the titular tailor of Riga, emigrated from Latvia to London around 1888, adopted the name Abraham Harris (without an “e” in the surname at that stage), and bought the pub where one of the victims of Jack the Ripper had last been seen? Could it really be true that a great-aunt of the narrator’s mother was killed by the Bolsheviks in Russia after a failed attempt to assassinate Lenin? Is it merely a coincidence that, during the Second World War, two German spies were assassinated along what was then called the North-West Frontier of India, around the same time the narrator’s father arrived there? The rest of the book unspools answers to these and other questions about the far-flung forbears of “Jonathan Harries,” and also about the life history of the narrator himself. In the process, the novel not only intermixes fictional and historical circumstances and personages, but also creates a rich blend of genres, including historical fiction, true crime, spy thriller, travel writing, and mock autobiography, among others.

The novel starts with the story of Abram Isakowitsch, the Latvian “tailor” who was, as it turns out, no ordinary tailor, but rather “an expert in fitting people for a wooden overcoat.” Like the other family forbears included in the narrator’s account, including his parents, Abram’s particular skill-set can be traced back to a Jewish sect of assassins called the Sicarii, whose weapon of choice was a type of dagger called a sica. (In both Spanish and Italian, the word sicario means assassin or hit man.) Two sicas, one from his mother’s ancestors and one from his father’s, get passed down to the narrator as family heirlooms, just before he has occasion to use them while serving as a mercenary in the Central African Republic. Indeed, it would be an understatement to say that the narrator takes naturally to the sica. Rather, for him, as for all of the family members whose stories he assembles, it seems that world-class knife skills are a kind of trans-generational muscle memory—to the point where practice is almost beside the point. Such instinctive capabilities strain credulity, even in a text that places no great store in coming across as credible. What is more, the novel’s treatment of a family of natural-born sicarias and sicarios serves to make light of, if not glorify, violence and murder, even though it casts the family’s actions as warranted by war or motivated by considerations of poetic justice.

Harries’ cross-generational family saga covers a lot of ground, both temporally and geographically. To help readers keep track of the multifarious characters, settings, and incidents involved, the author begins each chapter with a headnote specifying the place and date of the action, summarizing the main events portrayed, listing the dramatis personae involved (complete with bionotes and birth and death dates), and previewing other “notable names”—that is, historical references—brought up over the course of the chapter. This organizational device enhances the accessibility and immersiveness of the novel, enabling readers to get up to speed, quickly, on the historical circumstances in which the author’s assassins fictionally intervene. The result: a quirky revisioning of history from the vantage point of a family that, in this genre-bending and -blending account, has played a behind-the-scenes role in shaping the world we only thought we knew.

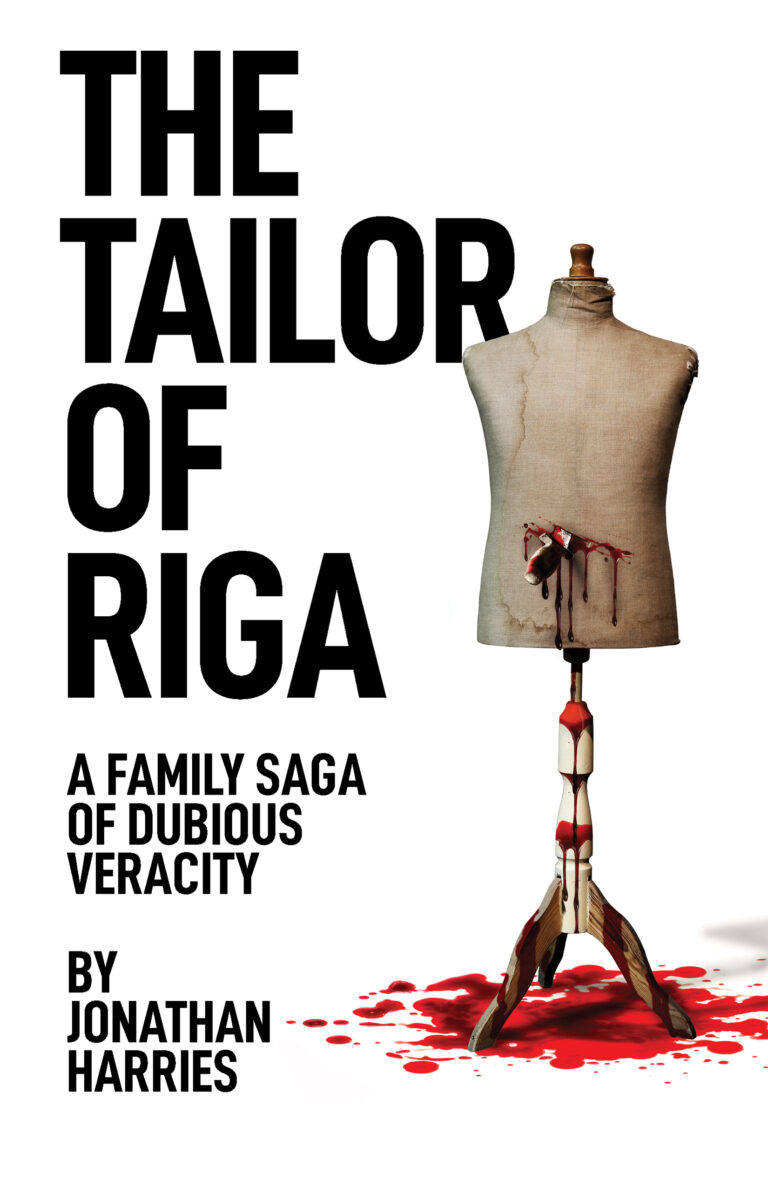

Jonathan Harries’ inventive novel THE TAILOR OF RIGA takes shape as a fictional family memoir, blending fiction and history with patently made-up tales of intrigue and assassination that afford fresh perspectives on world-historical events.

~David Herman for IndieReader