Seth Godin is the author of 18 books that have been bestsellers around the world and have been translated into more than 35 languages. He writes about the post-industrial revolution, the way ideas spread, marketing, quitting, leadership and most of all, changing everything. You might be familiar with his books Linchpin, Tribes, The Dip and Purple Cow.

In addition to his writing and speaking, Seth founded both Yoyodyne and squidoo.com. His blog (which you can find by typing “seth” into Google) is one of the most popular in the world.

He was recently inducted into the Direct Marketing Hall of Fame, one of three chosen for this honor in 2013.

Recently, Godin once again set the book publishing on its ear by launching a series of four books via Kickstarter. The campaign reached its goal after three hours and ended up becoming the most successful book project ever done this way.

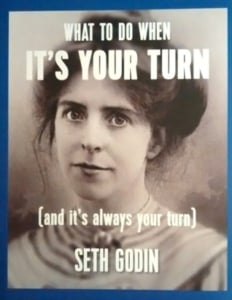

His newest book, What To Do When It’s Your Turn, is already a bestseller.

Loren Kleinman (LK): Two years ago you launched a series of four books via Kickstarter and reached your goal in three hours. Why decide to self-publish now and fund your projects through Kickstarter? How did this campaign relate to the thesis of your most recent book What To Do When it’s Your Turn?

Loren Kleinman (LK): Two years ago you launched a series of four books via Kickstarter and reached your goal in three hours. Why decide to self-publish now and fund your projects through Kickstarter? How did this campaign relate to the thesis of your most recent book What To Do When it’s Your Turn?

Seth Godin (SG): There were two goals: A) To show other authors how this platform could turn a following into a mechanism for making books in a new way… to find books for readers, not readers for books. And B) To make a statement to the publishing/bookselling world about adopting a book that had a proven audience. Generally, traditional book publishing is based on hope, the clean slate. In this case, an author with a permission base had the chance to organize the readers in advance…

My new book, What To Do When It’s Your Turn takes this a step further by being 100% based on the audience connection. No bookstores, no online bookstores, no single copies. A book to share, for people who want to share.

“The thing is, book publishing has also always been a lousy industry from an investment point of view, low return on equity, slow growth. It’s been anti-industrial.

Now, of course, there’s a new opportunity.”

LK: Can you define “industrial propaganda? How does it force us to “stand out, not fit in”? How does The Icarus Deception argue this point?

SG: Industrialism made our culture. It took us from mud huts to private jets, from a handwritten diary to a blog read by millions. Industrialism is based on repeated, improved effort to maximize productivity. It’s about average stuff for average people, in quantity.

It actually forces us to fit in, not to stand out! Because when we fit in, as workers or as consumers, the industrial system can profit.

LK: Does traditional book publishing fall into the realm of industrial propaganda? What does that mean to writers?

SG: Traditional book publishing has always been a shining light of individualism, the work of a single person with something to say, amplified by an institution. The thing is, book publishing has also always been a lousy industry from an investment point of view, low return on equity, slow growth. It’s been anti-industrial.

Now, of course, there’s a new opportunity, because the mass approach of most other forms of media is fading, fast, and books have always been the long tail!

LK: Is social media marketing a way to feed people’s need for instant reassurance? How so?

SG: I think the numbers we see of shares, of likes, of viral spread can become a tiny endorphin rush if we let it. We get hooked on pressing that lever over and over, to be reassured that we’re good, or interesting, or successful.

But all that pressing the lever does is make us fat, not important or useful. It keeps us from doing work that matters.

LK: Do you think most social media is propaganda? Is society lost in social media’s false promise of love and acceptance?

SG: Propaganda is generally something that’s done to us by an outside agency for gain. In the case of social media, it’s mostly something we do to ourselves, the acceptance culture whittled to a sharp point of a simple set of numbers and some banality.

LK: I love that you celebrate love in What To Do When it’s Your Turn. But you bring up an important perspective: that art is just another language of love; that it’s embracing and choosing ourselves. This choice, though, is it celebrated by marketing companies? Or do they use love as a metaphor of cruelty?

SG: Marketers tend to become selfish jerks when given the chance. I’m afraid of putting them in charge of love.

LK: What’s the infinite game?

SG: James Carse named it. It’s the game we don’t play to win; it’s the game we play to play. It doesn’t have a time limit or a scorecard, but instead benefits us merely for playing. Raising kids is an infinite game, so is collaborating with people we care about.

LK: In Steven Pressfield’s The War of Art he talks about the idea of resistance, or in other words how fear keeps us from working, from creating. You also talk about this type of fear and how it demotivates us. Is the idea of motivation, of getting motivated a myth?

SG: Motive as in move. And yes, we must move.

The myth is that we need a fancy trick, or an external one. That reassurance can eventually cause us to move. That’s a trap.

We become professional when we realize that movement is our job.

LK: Do you consider yourself indie in all aspects of life (i.e. writing, work, love)? Why or why not?

SG: Well, I don’t live in Brooklyn. Or have interesting facial hair.

But, when I can, I’d rather forge a path than follow one.

LK: Why does change hurt so much? And why does it take guts?

SG: Change might not work. That’s why we find it interesting. All humans associate, at some level, change with risk, risk with failure, failure with death.

So change might be death.

LK: How are self-published authors changing the traditional publishing landscape? How are they changing the way readers read and choose titles?

SG: Self-publishing is not merely a new way to get to the market. Self-publishing is the responsibility of choosing oneself. And that changes everything, completely and forever.

LK: How did you know it was your turn? And what did you do?

SG: How could it not be my turn? So many privileges, so much leverage. How dare I (how dare we) waste it?