Vincent van Gogh painted. His younger brother Theo supported him, corresponded with him, and worked desperately to convince others of his talent. Now both men are dead, and Theo’s widow Johanna is left with an overwhelming inheritance: a son to raise; hundreds of canvases and drawings; hundreds of letters filed away; and her dead husband’s conviction that Vincent van Gogh was a revolutionary who will one day be known as a leading light of the art world.

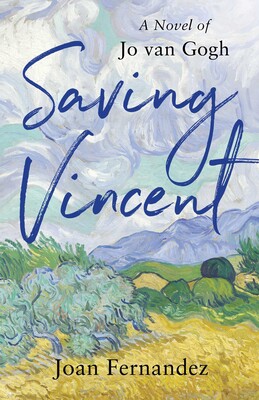

Joan Fernandez’s SAVING VINCENT draws on rich material. The life of Johanna (“Jo”) van Gogh-Bonger has been told a few times before, but it’s well worth revisiting. The placid canvases that now lounge upon museum walls and can seem so distant to a modern audience (removed, as we are, by the dramatic iconoclasm of post-modernism) are set back into the context of the late 19th century, with its “iron-fisted street fighting between Paris art dealers.” With Europe emerging into a recognizable modernity, technology is also changing; when a “gust of stale air [sweeps] the stink of manure and gasoline” through an open door, the reader is reminded of both the agricultural economy that overwhelmingly persists and the new petrochemical economy already putting automobiles on the road.

Social change is not far behind. Jo’s work is fundamentally revolutionary, as one fellow socialist remarks to her, “You are the only female art dealer in Holland. Perhaps in all of Europe!” But her journey as a protagonist is still primarily one of grief. Again, the historical material is rich in supply: as was evidently the case in reality, Jo is surrounded by crates of paintings and drawers of correspondence, forced to carry the physical reminders of her dead husband and brother-in-law. These political and personal arcs are well-paced and vividly drawn. There are plenty of scenes in which Jo openly confronts the blustering, authoritative men who try to exile her from the masculine world of high art, but the small, telling exchanges are equally effective. When Jo thinks of Sara de Swart, she recalls her as a sculptress; her brother Dries glosses, “Rodin’s lover.” Despite the fury Jo feels when confronted with misogynies great and small, SAVING VINCENT is still sensitive enough to show that she herself is not immune to the prevailing ideas of her culture. Jo still believes that “[a] mother’s first duty [is] to raise a strong, healthy, good-natured son” and that she must (almost compulsively) honor the wishes of her dead husband, in both the rearing of their only child and in the shepherding of Vincent van Gogh’s artistic legacy. The question of agency, both personal and political, is the spine of the text.

SAVING VINCENT also contributes to the rehabilitation of van Gogh’s character. The stereotype of the mad artist already hung about Vincent soon after his death (and indeed, may have been used for marketing purposes). But Jo in the text, as well as the text itself, work tirelessly to recall that the man was “not a romantic martyr” but a man: sometimes depressed or abrasive, sometimes sensitive or funny—a hard worker who cared deeply about the working class. Especially by including a few choice quotations from the painter’s published letters, SAVING VINCENT demythologizes the mad artist while reminding the reader that historical memory, of both art and of people, is not a matter of chance but one of deliberate choices by human beings—with their own needs, desires, and lives.

Joan Fernandez’s SAVING VINCENT, like the art of its eponymous demiurge, brilliantly evokes both the dignity of the mundane and the fire of revolution at the turn of the 20th century.

~Dan Accardi for IndieReader