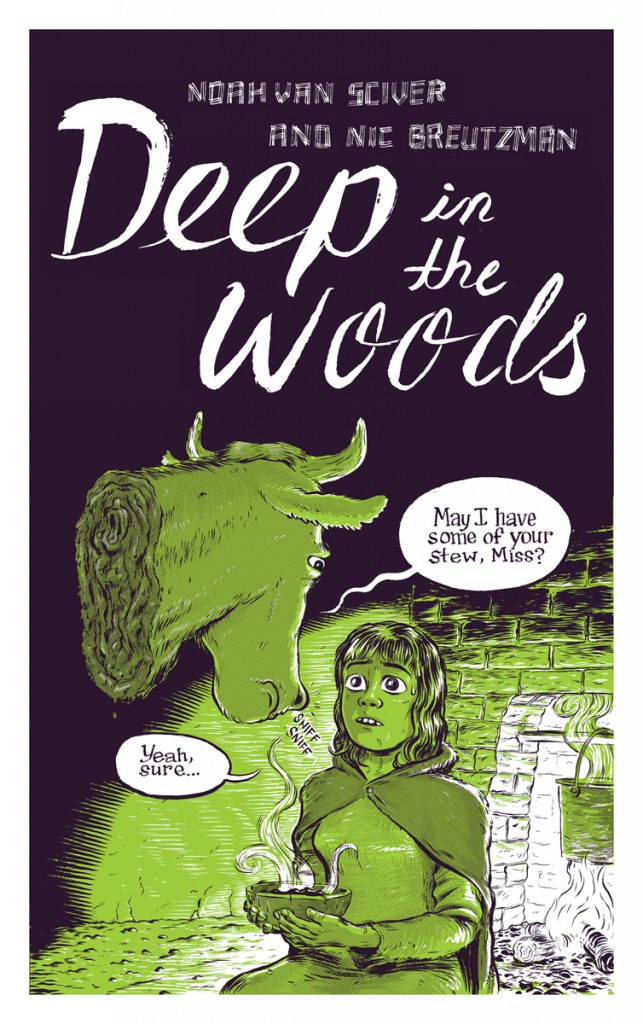

The over-sized newsprint style comic book “Deep in the Woods” is a collaborative double feature by Noah Van Sciver and Nicholas Breutzman, two exceptionally talented comic writers and artists possessing their own genuinely distinctive styles, who each contribute an original story channeling the ominous gravity found in the grimmest of fairy tales and urban myth.

Van Sciver and Breutzman’s respective visions prove a remarkably striking balance, both thematically and visually; each half is individually cohesive and strong, but presented back to back they handily exceed the sum of their parts through both their similarities and their substantial differences. Both tales revolve around one of the most archetypal figures in folklore and fable, the innocent and vulnerable young girl confronted by hostile elemental forces. They also portray how these encounters lead their youthful protagonists to a discovery bringing them some form of clarity or personal revelation, though in markedly contrasting ways.

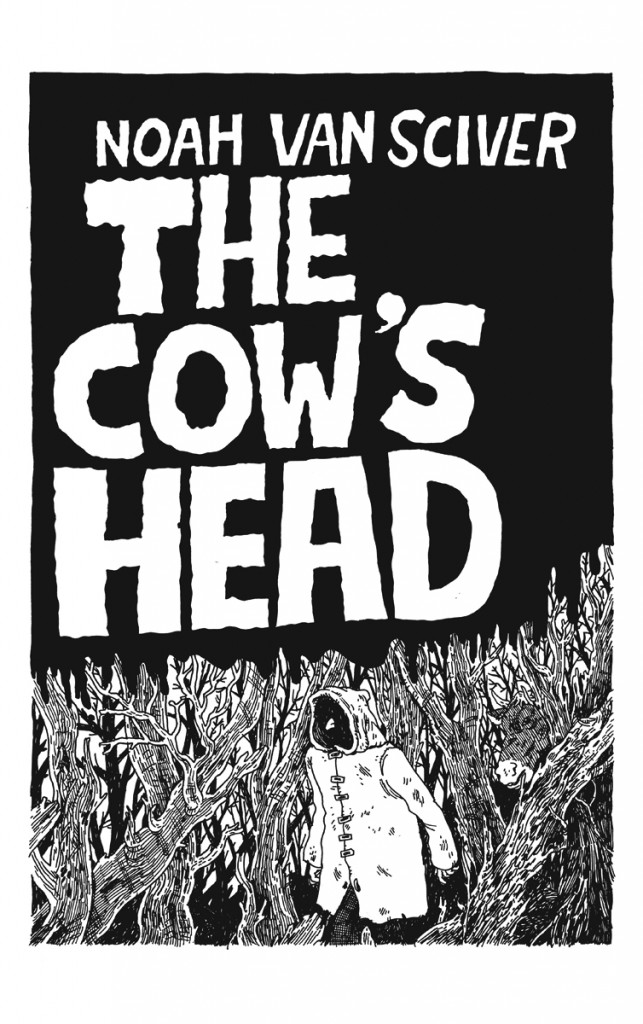

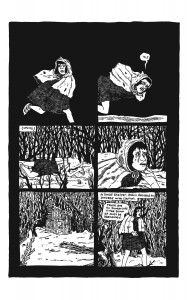

Van Sciver’s comic “The Cow’s Head”, which begins the book, is a story set in the mythic, timeless dominion of folklore. The central character is Robin, a young girl living a harsh, indigent life of struggle and abject poverty, spending her days dutifully caring for her father who is consumed by alcoholism to the point of infirmity. He is too deeply and intractably immersed in a drunken haze to protect her when she is eventually driven away from her own home by her pitiless and wrathful stepmother, another classic archetype drawn from fairy tales and fables down the ages.

She regards Robin’s presence in their dilapidated shack of a domicile as a mere nuisance, and after Robin overhears her intention to expel her from their home she runs into the forest, chancing a hasty escape over whatever other malevolent fate she fears may await her.

The forest is populated by sinister woodland spirits, whom she eventually eludes to take shelter in a seemingly abandoned shed nestled in it’s murky depths. She is shortly joined by a mysterious, ghostly apparition which proceeds to test the limits of her selflessness and altruism over the course of their shared night.

As morning breaks, Robin discovers that her long dark night of the soul in this wicked belly of the woods was a necessary experience for her to discover her own path toward a life beyond her past existence of resolute misery, however daunting and uncertain the journey before her might be.

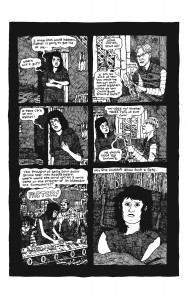

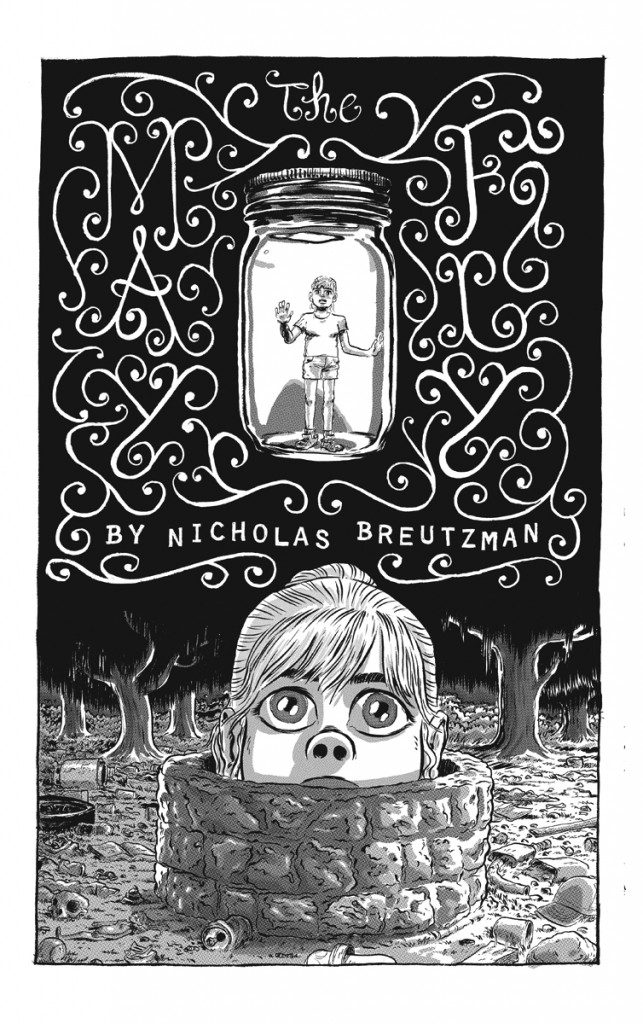

While “The Cow’s Head” exists outside of any specified time or sense of temporal reality, Breutzman’s “Mayfly” is very much of the present day. It tells the story of Sammy, the prototypical young girl at the center of the story, a doe eyed innocent who lives in a desolate rural wasteland the population of which seems to be composed of amphetamine and alcohol addled vagrants. She is joined by two brothers, bluntly identified by their t-shirts as Tim and Tom, grotesque in their physicality with naked eye balls dangling by a single optic nerve from their misshapen crescent faces.

The three of them are soon off on their own bizarre hero’s journey, involving a trek through the forest to retrieve their despondent grandfather from the bottom of a well he has retreated to in some hopeless fit of depression, as well as a side trip to a menacing witch who resides in the dark bowels of the woods and dispenses narcotics to the local doped up denizens. Sammy is casually abandoned by Tim and Tom, left to approach the witch alone. It is only once she has confronted and transcended her fears of the darkness within the foreboding heart of the woods, and the possible accompanying temptations, that she returns home to discover a gift left to her which inspires her own quiet epiphany.

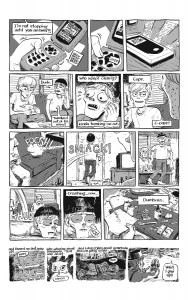

Breutzman also contributes a bonus comic strip adapted from a brief Mark Twain short story which unfolds on the bottom of the pages throughout “Mayfly”. It’s a brisk and concise tale of forbidden love and it’s eventual deadly aftermath, a sort of existential ghost story which fits perfectly into the larger tone and atmosphere of the stories it accompanies. Just as both “Cow’s Head” and “Mayfly”, it ends on a note at once resolute and satisfying, yet with a poetic ambiguity.

The larger format of the book serves the work beautifully, bringing out the meticulous attention to each vivid detail clearly dedicated to every panel, and the depth of rich textures both artists achieve through their own particular and arresting visual sensibilities.

“Deep in the Woods” was published by 2D Cloud. It is 30 pages, 11″ by 17.5″, and can be purchased for six dollars.