Shortly after returning from Pakistan to Texas with his new bride Zuleihka, Iskander fulfills the obligations of their marital contract, providing Zuleihka with the two things she most desired: a car and a piano. The used car has a busted radio and the used piano is minus a stool, but Zuleihka is touched by her husband’s commitment to his promises, and his desire to provide for her. The daughter of a VHS-bootlegger, Zuleihka is content with little. Longing for a piano as a child, her beloved Papajaan scrimped and bartered in order to get her a busted Casio keyboard. He was emotionally-tuned to her, and this made Zuleihka feel rich. This attunement is the primary thing lacking in her new marriage. “Interesting,” is Iskander’s standard response to anything Zuleihka says, before steering the conversation to a topic more to his liking. He grew up in the States and takes it upon himself to school Zuleihka in the areas in which he sees her lacking (such as politics and U.S. history), oblivious to the shock of changes thrust upon her, or any possible interest she might have in things outside of what he sees as appropriate for a Muslim wife.

On a hike around the neighborhood, Zuleihka is befriended by Marianne, an older, single mother who manages a restaurant. As the women grow closer, Zuleihka finds her ideas influenced by Marianne’s independence, and she begins to confess her growing discontent with her marriage. When Marianne abruptly leaves the state in pursuit of a relationship, Zuleihka is emboldened to hang out her shingle for piano lessons. On the threshold of giving birth, new doubts about Zuleihka’s life creep in: “Maybe that’s what it is, that she can never be sure of her own position in this post-racial, post-colonial, post-modern, post-everything world in which she gives birth to her son,” Mallick writes. When baby Wasim is a toddler, Zuleihka meets Patrick, a parent from daycare, at his child’s birthday party. Patrick confesses he’s always wanted to learn to play the piano and they commence with lessons. But it isn’t long before their feelings for one another drown out the music.

THE BLACK-MARKETER’S DAUGHTER is a key-hole look at a few different things: a mismatched marriage, the plight of immigrants in the U.S., the emotional toll of culture shock, and the brutal way Muslim women are treated, especially by men from within their own community. It isn’t until Zuleihka begins to strain against her bonds that she understands the extent of her imprisonment. As Zuleihka is later told by an ally, women like her “‘arrive at this country by marriage, they think they’ll be free from the lives of their mothers and grandmothers, and instead, they are told, ‘You’re mine, I can do with you whatever I want.’”

After a slow start, THE BLACK-MARKETER’S DAUGHTER picks up speed in its second half, but even then, the writing remains detached and somehow clinical. Things are described flatly; scenes don’t come alive before the reader’s eyes. Information, even dialogue, is delivered in huge blocks. A reader might begin to feel a little like Zuleihka, subjected to an education she didn’t know she lacked, and isn’t sure she needs.

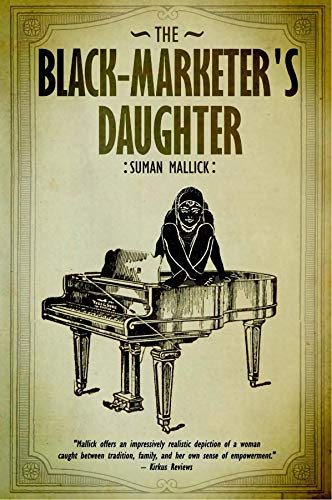

Author Suman Mallick advocates for the rights of Muslim women within their relationships and on that count the THE BLACK-MARKETER’S DAUGHTER largely succeeds. Titling it—defining the heroine by her relationship to a man rather than as a woman in her own right—suggests how deeply ingrained that inequality can be.

~Michael Quinn for IndieReader