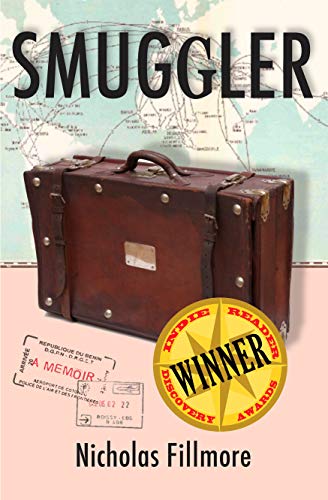

Smuggler was the winner in the True Crime category of the 2019 IndieReadwer Discovery Awards, where undiscovered talent meets people with the power to make a difference.

Following find an interview with author Nicholas Fillmore.

What is the name of the book and when was it published?

Smuggler was published Jan 1., 2019.

What’s the book’s first line?

“The highway, a graded red clay road raised right on top of itself, went north into the interior, through the bush—around armed checkpoints, beyond the Africa of hotel bars and jelly cocos, into an immensity.”

What’s the book about? Give us the “pitch”.

When twenty-something post-grad Nick Fillmore discovers the zine he’s been recruited to edit is a front for drug profits, he begins a dangerous flirtation with an international heroin smuggling conspiracy and in a matter of months finds himself on a fast ride he doesn’t know how to get off of.

After a bag goes missing in an airport transit lounge he is summoned to West Africa to take a fetish oath with Nigerian mafia. Bound to drug boss Alhaji, he returns to Europe to put the job right, but in Chicago O’Hare customs agents “blitz” the plane and a courier is arrested.

Thus begins a harried, yearlong effort to elude the Feds, prison and a looming existential dead end…. Smuggler relates the real events behind [the book and hit Netflix show] Orange Is The New Black.

What inspired you to write the book? A particular person? An event?

One inspiration was a Chicago Tribune article summarizing my allocution at sentencing. I’ve always kind of hated the sanctimony of cops, in the movies anyway; like, “what’s it to you?” I got the same feeling reading this newspaper article, which talked about a “day of reckoning” and basically made me out to be a privileged white boy caught in a black man’s trap. I suppose that’s good reading and has a salutary effect on public morals, but it’s a gross oversimplification of the facts. And I realized pretty early on that I needed to rectify that. It was a long time, though, before I actually started writing the memoir in its present form. That required a little bit of perspective. About a half a dozen years. And another half dozen to take it through various drafts.

What’s the most distinctive thing about the main character? Who-real or fictional-would you say the character reminds you of?

I started fooling with a screenplay in prison around 1998 or 9, recognizing my story’s inherent dramatic possibilities, then put it aside for a number of years after I realized that all the inner action demanded something more novelistic.

Much of this time I puzzled over how I might present an unsympathetic protagonist (myself) who despite his villainy is not exactly an anti-hero, but more like a frustrated idealist.

I’ve been asked elsewhere to clarify this distinction between anti-hero and frustrated idealist. That’s a little vague, is it not?

I think of the anti-hero as possessing an unconscious quality. At bottom he is deeply pragmatic, which precludes any deeper considerations of right and wrong.

The frustrated idealist, conversely, is someone who has made the conscious choice to do wrong (for its own sake). Morality is central to his outlook; thus, his choices are said to be immoral, as distinguished from the merely amoral choices of the anti-hero. The frustrated idealist exists inside society, as opposed to the anti-hero, whose unconcern allows him to float above consequences.

Some of this may be my own peculiar outlook. In writing my own character, it felt necessary to distinguish the blithe opportunist of Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Times from an anguished Raskolnikov; the picaresque from the tragic.

I wasn’t smuggling drugs just for the money. Or entirely for the experience. But partly out of a sense of injustice, and a deeply misdirected desire for revenge….

In Smuggler I’m a little coy about my sense of injustice. That’s partly temperamental and partly an artistic choice. And partly the desire to have my character retain a sense of agency, not just be reactive and blaming. Suffice it to say he is aggrieved. Only from time to time does his frustration spill over into words:

“In another place and time I might have raised a fist. Or manned the barricades. But in our post-sixties era, cowed by Reagan and Bush Sr. and defeated by a rhetoric so inane that to oppose it would seem stupid, we resorted to punk rock’s effete gestures: ‘Don’t know what I want, but I know how to get it.’”

What’s the main reason someone should really read this book?

Well, it is a story for our times: of the struggle to break out of one’s routine; to feel alive—to make oneself felt, more accurately. Of course it’s also about the pitfalls that go along with that.