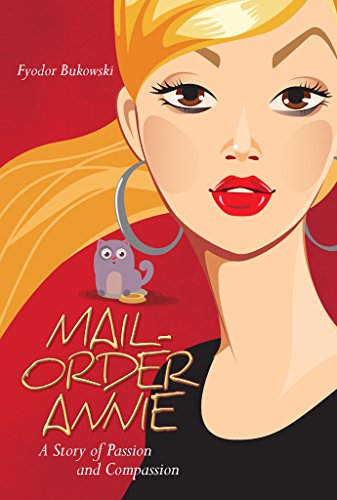

The main character in MAIL-ORDER ANNIE is a trailer park-dwelling English teacher named Frank who is afflicted with considerable sexual frustration. Frank’s life revolves not around any noble aspirations of teaching and sparking a literary interest in his students, but around bedding a trophy girl. But having steeped, so to speak, the reader in this beyond-seedy setting, Bukowski transcends the Henry Miller world he so at times strains to recreate by changing Frank’s quest from seeking meaningless sex to seeking actual love.

In the introduction to this book, Fyodor Bukowski—the author’s pen name—acknowledges as his literary influences Fyodor Dostoevsky, Charles Bukowski., and Henry Miller. But he should also acknowledge David Mamet and his play, Sexual Perversity in Chicago. Certainly, Bukowski uses the trappings of Henry Miller, with Bukowski’s trailer park deadbeats standing in for Millers’ drinks-cadging bums of 1930s Paris who, as with Miller’s compatriots, have no ambition beyond the next sexual conquest. But apart from Mamet’s bed-hopping yuppies, updated for the film adaption of his play, re-titled About Last Night (1986), Bukowski shares the same theme as the playwright’s in having his decidedly-non-yuppie Frank seek true love.

For those who tire, as did George Orwell who largely admired Miller, of the latter’s cosmic ramblings (what Orwell, a writer who demanded clarity if there ever was one, criticized as “a Mickey Mouse world where ordinary rules don’t apply”) the reader will get only the Miller of the frank sexual talk. I know of no other book in recent memory so fixated on strip clubs and the “outlets” they provide lustful customers. And Bukowski has the dubious achievement of out-performing—for lack of a better word—Henry Miller in the profanity department.

But Bukowski has a gift for irony that Miller never had. His setting, the post Cold War world, abounds in them. Perhaps the last remaining illusion of Cold War America, that Russian women are hairy shot-putter types—more Khrushchev than an Ian Fleming Russian femme fatale—is demolished by those advertised in Russian mail-order-bride catalogs who match any super-models the West has to offer (the influx of Russian women into the US since 1991 now work as super-models).

Frank has a father who embarrasses him with his communist beliefs, which Frank attributes to an “unhinged brain” brought on by “too many years of working in that factory and having to ask the boss if he could leave his machine to go take a piss.” At the same time, the father enjoys the fruits of his hated capitalist system, owning two expensive cars and a “Tahj Mahal” type house on the lake. On this matter, Bukowski is being doubly ironic, for one of the realities Soviets refused to believe during the Cold War as nothing more than capitalist propaganda was that Americans owned their own cars; the other was that, despite the supposedly leveling nature of Soviet society, the upper echelons were given their own car and a nice house by the sea as does Frank’s father; the father is more a Soviet “communist” than he realizes.

Despite everything being political in the old Soviet Union, it is American women, who in what Bukowski pithily labels “job interview” fashion, demand to know Frank’s “religion and political views” before taking the date to the next level. But the strongest irony, which is in essence one of the themes of the book, is that Frank is considering leaving what he believes to be love-crushing America to find a mail-order-bride he fantasizes about, in of all places, the Ukraine; this country that supposedly contains his dream girl was, under Stalin’s rule, a hell on earth where he starved to death 7,000,000 farmers in the 1930s, and until his death in 1953, dumped Ukrainian citizens into Gulags. Ukrainians, then and now, wanted out to get to America; Frank wants in.

Bukowski may not know it, but his true gift is an anti-Miller-like irony. He is too grounded a writer to fly off into Miller’s god-like ramblings (Orwell pithily said that “Miller needs to stop pretending to be God; for God only wrote one good book”), and when he stops trying to emulate Miller’s profanity, he is a nuanced writer.

~Ron Capshaw for IndieReader